*******************************************

I have not received any encouragement or inducement from anyone to write about or discuss any information related to the Manchester Attack. All research discussed is exclusively my own and based solely upon information freely available in the public domain.

*******************************************

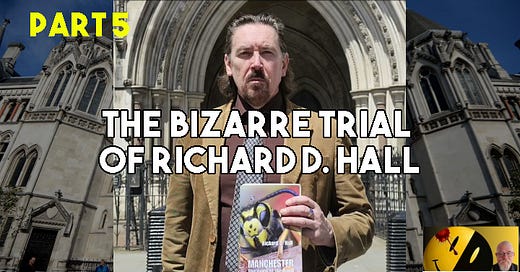

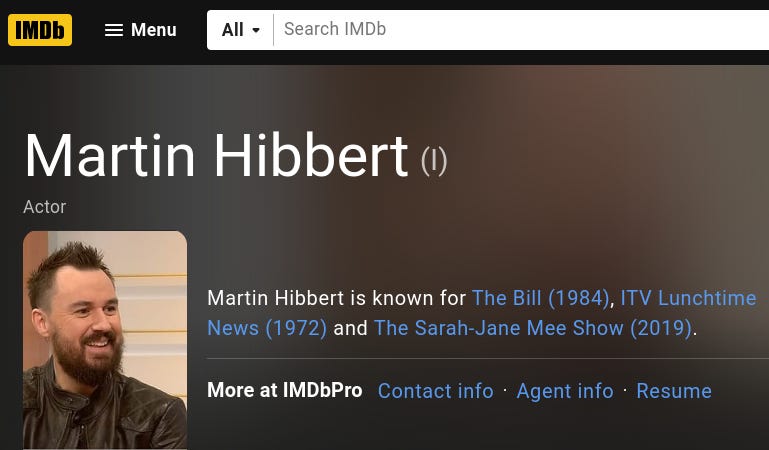

Please read Parts 1 - 4 for a full report on the court proceedings in the civil claim for harassment and GDPR breaches brought against investigative journalist Richard D. Hall by two of the reported victims of the so-called Manchester Arena bombing.

Hall reported the evidence that shows the Manchester Arena bombing was a victimless, hoaxed false flag attack. You can get a copy of Hall’s book Manchester: The Night of the Bang for FREE from his Richplanet website or you can support Richard D. Hall by purchasing a paperback copy.

I was among the many people who found the evidence Hall reported compelling. I subsequently explored the wider implications of the case, the propaganda setting, and presented additional damning evidence in my book The Manchester Attack: An Independent Investigation—also freely available as a PDF.

Following cross-examination of the prosecutions witnesses by Hall’s defence barrister—Mr Paul Oakley—the prosecution, led by barrister Mr Jonathan Price, called Richard D. Hall to give evidence. Hall was asked by Mr Price to confirm his written, signed testimony submitted to the High Court. When asked by Mr Price, Hall confirmed he was an investigative journalist, author and documentary film maker.

It was established by Mr Price that both Hall’s book and his accompanying documentary had been published—and made available—in the public domain by May 2020. Mr Price drew Hall’s attention to the “infamous” photo of Mr Hibbert and Eve Hibbert, reportedly taken in the San Carlo restaurant on the night of the attack. Hall was invited to acknowledge the claimed importance of this image, to which Mr Hall said “alleged.”

Mr Price sought clarification from Hall. Hall stated that he disputed Mr Hibbert’s claims regarding when the photograph was taken. Hall added that he was not aware of any evidence establishing that it was, in fact, taken on the night of the purported bombing, adding it could have been captured at any time prior to the 22nd May 2017.

Mr Price asked Hall what he believed happened that night. Hall replied that the primary, physical evidence showed there was no bomb. Hall briefly explained some of the history of false flag attacks, mentioning Operation Gladio as an example of state orchestrated domestic false flag terrorism. Hall stated that a hoaxed false flag was entirely possible.

Mr Price mentioned the reporting of the BBC social media and disinformation correspondent Marianna Spring. He stated that she had reported that Hall had more than 80,000 followers and had garnered more than 16 million views across his YouTube channel before it was shut down. Hall, perhaps anticipating where the line of questioning was heading, interjected—which Mr Price allowed—and stated his YouTube channel was not monetised and had not, in any event, carried any of his work on the Manchester hoax.

Mr Price asked Hall if he believed any aspect of the claimants’ account of the bombing and how they sustained their injuries. Hall replied that if he could see some evidence substantiating their claims he was willing to revise his so-called “staged attack hypothesis.” Hall added that, as it currently stands, the evidence shows there was no bomb and he could not, therefore, accept any aspect of the Hibbert’s claims with regard to how, where and when they sustained their injuries. Hall stated that it was “unlikely” that such evidence could possibly emerge, therefore, he maintained his scepticism of the claimants’ accounts.

Mr Price acknowledged that the authorities and the media sometimes get things wrong. He then asked Hall to “imagine” that the official account of the Manchester Arena bombing was true. Thus began a discussion which Hall repeatedly referred to as “hypothetical.” As an observer, the hypothetical nature of Mr Price line of questioning surprised me. I had not expected a hypothetical argument to be made by a prosecuting barrister in a High Court of Justice trial.

Mr Price asked Hall if he felt any compassion for the victims of the bombing that was being discussed in hypothetical terms. Obviously, Price was alluding to his clients claimed experience and their injuries.

Hall replied that he felt compassion for anyone suffering life limiting injuries or disabilities. He added that both claimants had “obviously” sustained serious injuries. Hall then observed that did not change the fact there was no evidence of a TATP shrapnel bomb.

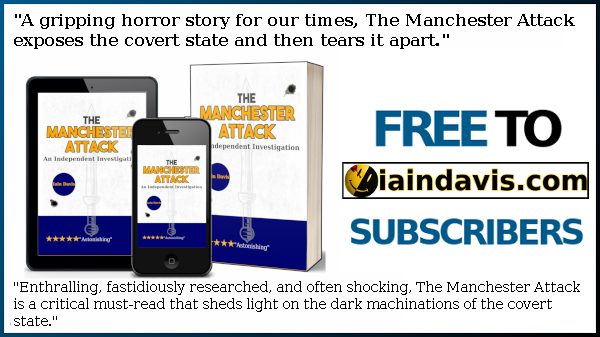

Mr Price then drew Hall’s attention to the fact that Hall had reported Mr Hibbert’s listing as an actor on the IMDB website—a database and promotional website for the entertainment industry. During his testimony, Mr Hibbert had claimed that he did not create that listing and it was nothing to do with him. I noted, at the time, that Mr Hibbert did not say he had done anything to have the IMDB listing removed.

Mr Price put it to Hall that he was trawling the public domain, finding snippets of information and drawing the wrong conclusions. Mr Price suggested that Hall’s contention that Mr Hibbert was an actor, who had appeared in an episode of the ITV police drama—The Bill, was an example of Hall’s shoddy journalism.

Post-publication of his book, Hall has publicly stated that he no longer thinks Mr Hibbert appeared in The Bill. In the High Court, in response to Mr Price’s questioning, Hall pointed out the fact that Mr Hibbert is still listed as an actor on the IMDB website.

Mr Price put it to Hall that every aspect of his reporting on the alleged Manchester Arena bombing was, in fact, wrong. Mr Price stated that everything his clients said about events that night was true and that Hall had caused gross offence and distress by questioning their accounts. Hall replied that there is no evidence of a bomb.

Hall went further—again Mr Price allowed Hall to expand. Hall stated that primary, observable physical evidence outweighed witness accounts. Hall argued that witness accounts were only credible if they were supported by physical evidence and could not be considered substantive if they were wholly contradicted by the physical evidence.

Mr Price moved on. He acknowledged that Hall was not subject to Ofcom regulation but then argued that Hall could not expect any protection as a journalist unless he acted responsibly as a journalist. Mr Price suggested that Ofcom defined these responsibilities. Mr Price drew the courts attention to the Section 7 of Ofcom’s broadcast journalism regulations dealing with fairness.

Mr Price spoke about how individuals, perhaps considered vulnerable, could be “at risk of significant harm”—according to Ofcom—if they featured in or were the subjects of unfair criticism in broadcast media reports. Ofcom suggests that broadcasters should conduct a “risk assessment” prior to broadcasting any reports that have the potential to cause “significant harm,” as defined by the government and its broadcast and online regulator: Ofcom.

Price asked Hall if he had conducted a risk assessment prior to broadcasting content which he knew, or could reasonably be expected to know, would cause “significant harm” to his clients. Hall challenged this assertion of claimed “significant harm.”

Hall stated, as a journalist, his primary public responsibility was to report the truth. Hall acknowledged that people would react to information he reported in many different ways but that he could not possibly predict, with any degree of certainty, what their individual subjective reactions might be. Hall further stated that journalists had a “responsibility” to report the truth and could not shirk that responsibility simply because they knew, or could reasonably be expected to know, that some people might be offended by their reporting of the truth.

Hall highlighted that, contrary to the claimants’ witness testimonies, he had chosen not to disclose any aspect of the trial to his nine year old son who did not know what his father was facing. He had made this decision, he said, because he did not want his son to worry or become distressed. Mr Price countered Hall by pointing out that Eve Hibbert is an adult. Hall reminded Mr Price that Eve has the reading age of a nine year old.

Mr Price moved on swiftly. He next highlighted the subject’s, of any news report, right to privacy as defined by Section 8 of the Ofcom code. For the purposes of the Ofcom code, a “warranted” infringement of individual privacy can only be established if the journalist or broadcaster can show that the public interest “outweighs the right to privacy.” Hall responded by pointing out that the Ofcom regulations also clearly state that some infringements may be necessary in the public interest and Hall put it to Price that he was acting in the public interest by examining his clients’ accounts.

Price put it to Hall that his publication and broadcast of material related to the claimants was, in fact, unwarranted. He said Hall had not presented any evidence to show that infringement of his clients’ privacy was outweighed by the public interest. It should be noted, the summary judgement, secured by the prosecution, barred Hall from presenting this evidence.

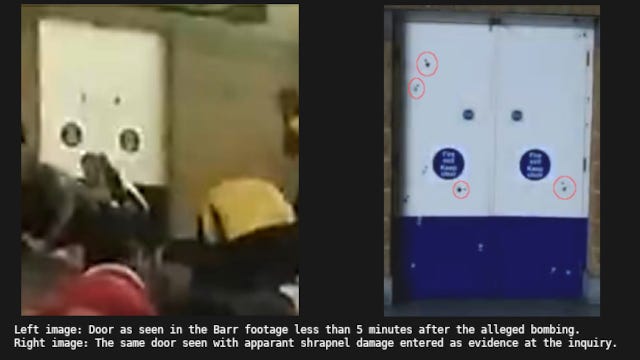

With regard to the evidence he had not been able to present, Hall responded by asking for leave to present to the court a still image, taken from the Barr footage, showing the completely undamaged merchandise stall—said to be well within the devastating 10 metre blast radius of a large shrapnel bomb. Both Mr Price and Mrs Justice Steyn were shown and looked at the image presented to them by Hall—shown below.

Hall asked if he could read a statement from another reported “victim” of the so-called bombing, Mrs Josie Howarth. Hall read her statement to the court:

We’d been sat waiting for the concert to end on some steps near the entrance. When the music stopped we stood up and went towards the foyer. Then the next thing I know, there was an explosion and the merchandise stand blew to pieces.

As was evident from the still image of the merchandise stall, this account, from a Manchester Arena victim, was, for whatever reason, false. Had a large TATP shrapnel bomb, of the type described in the official account, detonated anywhere near the merchandise stand, Hall explained to the court that it was not possible for it to have remained in the pristine condition observable in the image.

Hall continued, reporting to the High Court the numerous inconsistencies in the accounts given by Mr Hibbert about the bombing. For example, Martin Hibbert had claimed the bombing had occurred inside the main auditorium, which was untrue. Hibbert said that he was in the auditorium when the bomb went off, which was also untrue. He said he had brushed shoulders with the bomber inside the auditorium, which again was untrue. Hall highlighted that these false claims meant that investigation of the witnesses was fully justified.

A discussion was then held about the Parker photograph which was seemingly taken during the same time frame as the Barr footage. This photograph has been widely reported by the legacy media and Mr Price suggested it showed the aftermath of the bombing. Mr Price said a blood trail was observable and put it to Hall this contradicted Hall’s “hypothesis.”

When Hall initially reported on the image he reported the apparent blood trail (see below) observable in the photograph. Price picked up on this as evidence of a bombing. Hall countered by saying he wasn’t sure if it was real blood.

There are many reasons, explored in both Hall’s and my own book and in Hall’s later investigations, which show the Parker photograph does not capture the aftermath of a “real” shrapnel bombing. For example, the lack of any structural damage, undamaged lighting, the absence of any significant blood splatter or injuries consistent with shrapnel bombing, the insufficient number of alleged victims, etc.

Hall has never speculated, to any notable extent, what the red streak seen in the Parker photograph (above) consists of. Its composition is not among the points of evidence, seen in the photo, that Hall has examined to rationally demonstrate no bombing occurred. The fact that there is no body at the end of it is more relevant. Nonetheless, with reference to the observable red streaks across the floor, Mr Price asked Hall:

Do you have any evidence that it is not blood?

To which Hall immediately replied:

No, but do you have any evidence that it is blood?

Mr Price, rather dismissively, asked Hall who he imagined was behind this “conspiracy.” Hall stated that some members of the counter-terrorism police at Greater Manchester Police would have been involved in implementing the staged attack. Hall added that the intelligence agencies must have been involved in the hoax and the subsequent cover up but noted further investigation would be required to find out who the perpetrators were.

Mr Price hastily abandoned this line of questioning and spoke about the medical evidence and argued that a medical report by a Dr Soni provided evidence of Hibberts injuries. The report was written 3 years after the attack, for the purpose of claiming criminal injury compensation, and included references to Hibberts medical records.

Hall pointed out that this report does not provide primary evidence attesting to how, where and when Mr Hibbert sustained his injuries, nor any images or scans. Hence Hall’s application to see the relevant medical evidence from the actual time of the event.

With regard to an X-ray image of Hibbert which appeared in the media, Hall told the court he had it analysed by an orthopedic surgeon who said it appeared the person in the X-ray had no teeth, and therefore questioned whether the person in the X-ray was Hibbert. Mr Hibbert does have teeth, and in response to the surgeons statement, Hibbert claimed he was wearing a gumshield—for some reason—when the X-ray was taken. Hall told the court he was not a medical expert but thought that either the gumshield would be visible if it was obscuring the teeth, or the teeth would be visible through the gumshield.

Mr Price said Hall had effectively ignored the medical and other evidence presented by his client. He put it to Hall that his publication and broadcasts constituted grossly offensive actions that amounted to cruelty. Mr Price gave the example of Hall’s questioning of the “infamous” San Carlo restaurant photograph which captured his clients “treasured memories.” Price put it to Hall that he did not care about the impact his reporting had on his clients.

Hall stated the photograph was a very important piece of evidence because it was the only evidence presented by the claimants that supposedly substantiated their presence in Manchester, although it couldn’t substantiate their presence in the Arena and certainly not in the City Room. Therefore, it was, Hall argued, very much in the public interest to examine this photographic evidence.

Price asked Hall why he didn’t “just believe” his clients. Hall again responded by pointing out that his primary responsibility as a journalist was to report the truth. Hall stated that there was no evidence of a bomb and that he had searched every single one of the 806 CCTV images provided to the official inquiry and that Mr Price’s clients were not observable in any of them.

Hall then challenged Mr Price. Hall suggested that rather than argue about his—Hall’s—interpretation of the evidence, the High Court could simply release the medical and CCTV evidence he previously applied for but was denied by the summary judgment ruling of Master Davison.

Mr Price didn’t respond and moved on.

Mr Price cited the numerous official investigations, reports, inquiry findings and rulings—such as the Saunders Inquiry reports and the summary judgement of Master Davison—which, Price argued, proved Hall’s opinions about the alleged Manchester Arena bombing were without foundation. Mr Price put it to Hall that he should accept these rulings and, if truth mattered to him, should report the official account.

Hall responded by pointing out that he had reported extensively on all of these findings and rulings. Hall then informed Mr Price that he had not only reported the summary judgement of Master Davison but had put a full, unedited copy of the entire ruling on his website.

Mr Price pressed Hall stating that he should accept all of these rulings. Price asked Hall if he disagreed with them all, including the ruling of the trial judge Mrs Justice Steyn—who previously rejected Hall’s application to appeal the summary judgement. Hall replied “yes” and confirmed that he questioned all of these official findings.

Hall suggested that the vast majority of people believe the official account as reported by the state and the legacy media but that does not signify they are familiar with all the evidence. Hall suggested that those unaware of the evidence he had reported could easily include judges and other officials of the state. Hall pointed out that he was far from alone in questioning the Manchester Arena narrative and referenced research by Kings College which suggests more than a quarter of UK adults hold similar views.

This concluded Mr Price’s cross-examination. Richard D. Hall was discharged from the witness stand by Mrs Justice Steyn.

I could hardly believe what I what I had just witnessed. Having secured the summary judgement—barring Hall from discussing the evidence showing that the Manchester Arena was a hoax—Mr Price’s cross-examination of Hall had not only led him to ask Hall to speculate about hypothetical scenarios but had left him embroiled in a debate about the evidence that clearly does show the bombing was, in fact, a hoax.

Not only that, Hall had managed to introduce to the High Court—with the court’s permission—a fraction of the evidence that the High Court had previously barred him from discussing. It seemed at every juncture, wherever Mr Price had invited Hall to acknowledge or accept the state’s account of the alleged bombing, Hall was able, by some means or another, to rebut the prosecuting barristers points by squeezing in a reference to the evidence.

It was notable that Mrs Justice Steyn—who informed the court she has read Hall’s book—did not interject and, when Hall asked, agreed that he could present some of his evidence to the court. Though admittedly only to a limited extent.

As I waited to for Mr Price’s summation, I was fascinated to hear how he was going to tie any of the cross-examination of Hall to the claims of harassment and GDPR breaches. For the life of me, I couldn’t see how the arguments presented by the prosecution related to the claim.

As we discussed in Part 1, it was hard to understand what relevance Mr Price’s summation had to the harassment and GDPR claims. Instead of focusing on the evidence presented during the trial, Mr Price seemed to be largely preoccupied with how the ruling of Mrs Justice Steyn might necessitate some case precedent reinterpretation of UK court’s reading of Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR)—protecting freedom of expression. Mr Price spoke about how this right may have to be re-balanced in respect to Article 8—right to respect for private family life—and Article 9—freedom of thought, conscience and religion.

With regard to harassment, Mr Price focused upon Hall’s “course of conduct” claiming that, in its entirety, it amounted to “harassment by publication.” He claimed that Hall had an arrogant approach to ECHR Article 10 and had crossed the line from reasonable freedom of expression to unreasonable criticism and pursuit of his clients, to the extent that it amounted to harassment.

There were a couple of points that stood out to me in Mr Price’s summation. He repeatedly had conversations with Mrs Justice Steyn about videos that preceded Hall’s 2020 publication of his documentary. This theme had cropped up frequently throughout the prosecution’s case. But Hall had not published or broadcast anything in relation to the claimants prior to 2020. This point, raised by the prosecution, often confused me. I may have misunderstood it.

As we discussed previously, Hall had originally tried to offer the defence of investigating a crime under the Prevention of Harassment Act 1997. In his summation Mr Price said that Hall had no possible defence of “investigating a crime” because Hall had not provided any evidence to the court to substantiate the existence of any crime. This seemed grossly unjust to me. Hall could not provide any evidence of a “crime” precisely because the claimants secured the summary judgement ruling all of his evidence inadmissible.

The trial concluded, more or less, with the closing summation of Hall’s defence barrister, Mr Oakley. Unlike Mr Price, Mr Oakley said that he would be focusing on the evidence presented in the trial and the timeline of events established in the High Court.

Mr Oakley said the prosecution had failed to provide any evidence of anything that could constitute harassment of the claimants. Hall could not be guilty of harassment simply by publishing criticism of information placed the public domain by the claimants. Most notably Mr Hibbert.

Martin Hibbert could not, in fact, control what criticism might come his way after making so many public statements. Nor, Mr Oakley added, could Mr Hibbert control fair use of any images he had agreed to be published, or images he published on social media.

Oakley said that the particulars of the claim were vague and pointed out that his client—Richard D. Hall—had offered a remedy in his reply to the letter before claim. He highlighted, when asked to specify what actions Hall had allegedly committed that could constitute harassment, Mr Martin Hibbert had been “incredibly vague” and could not identify any incidents at all.

Mr Oakley said that Mr Hibbert’s contention that he had seen a video from Hall in 2018 questioning his account of the bombing could not possibly be true because Hall hadn’t published anything about the claimants at that time.

Mr Oakley contended that Hall had acted reasonably at all times. He pointed out that when Hall unearthed and reported the evidence exposing the apparent Manchester hoax, he sent it to the Saunders Inquiry panel. Mr Oakley suggested to the court that Hall demonstrated responsible and “reasonable” conduct.

Mr Oakley highlighted that it was abundantly clear that neither Mr Hibbert nor Miss Gillbard had any awareness of either Hall’s work or his 2019 visit to the Miss Gillbard’s address until the summer of 2021. This, Mr Oakley said, was more than a year after Hall had published his work.

Mr Oakley stated that the claimants were not the subjects of Hall’s investigative journalism and were discussed relatively briefly in both Hall’s original book and documentary. Mr Oakley pointed out that it was only later, in November 2023, after the claimants had started pursuing Hall, that they were discussed at any length by Hall.

Oakley argued that while Mr Hibbert frequently collaborated with the (legacy) media, including the BBC and Marianna Spring, his client had declined to do so. He noted that Mr Hibbert actively sought to promote himself and his story with the media but that Mr Hall did not.

With regard to the July 2021 visit to Miss Gillbard’s address by Greater Manchester Police (GMP)—following allegations made against Mr Hall—Mr Oakley said GMP made door-to-door inquiries and no wrongdoing by Mr Hall—or any of his “followers”—was identified by the police. Mr Oakley stressed this episode had absolutely nothing to do with the “course of action” pursued by his client. The “allegations” were evidently unfounded.

Mr Oakley added, it was clear that matters had been stirred up, not by the course of action followed by Mr. Hall, but by the activities of the GMP. While noting that the police were simply making the proper and necessary inquiries, Mr Oakley again highlighted that Hall had no involvement in any of it.

In reference to Hall’s visit to Miss Gillbard’s address in 2019, Oakley asked the court to recognise that Hall’s conduct was ultimately of no concern to GMP. Hall did not do anything to harass the claimants, did not break the law in any other way and was perfectly entitled to conduct his investigation as he did.

Mr Oakley said that the “huge reaction” to the BBC Panorama episode (Disaster Deniers) was evidently the cause of distress for Eve Hibbert. Similarly, it was the “huge reaction” that Mr Hibbert cited as the source of his claimed “fear for his safety.”

Yet, Oakley again stressed, Mr Hall had absolutely nothing to do with the BBC Panorama episode and had pointedly refused to be involved. It was Mr Hibbert who had agreed to participate and, in doing so, it was Mr Hibbert who had contributed to the distress of his own daughter and his own, claimed fears. Again, Mr Hall was not involved.

Oakley then turned to the testimony of Miss Sarah Gillbard. He described the fact that Miss Gillbard had not seen either the letter before claim or Mr Hall’s subsequent offer of remedy as “gravely astonishing.” Mr Oakley questioned how such a case could ever have come to the High Court of Justice in the first place.

He suggested that it was obvious the dispute should have properly been dealt with by first going to the Information Commissioners Office (ICO)—with respect to the GDPR claims—and a trial could have been avoided altogether had the claimants—Miss Gillbard as litigation friend for Eve Hibbert—been properly informed about proceedings by her own legal representatives. Oakley added that should such a case go to trial, “some quiet county court would have been appropriate.”

He questioned why the prosecution had brought the trial to the High Court of Justice. Mr Oakley noted the prohibitive costs involved for his client and how the whole case seemed entirely unnecessary.

It was evident, Oakley argued, that Eve was worried about the “stalker man” for no reason other than her parents had described Hall to her as a stalker without any justification whatsoever. Oakley referenced the letter from Express Learning about dealing with Eve’s emotional response to a program her father—Martin Hibbert—wanted to appear in but that his client—Mr Hall—did not.

Oakley stated that it was “quite remarkable” that Martin Hibbert brought this action against his client—complaining of the alleged actions of Hall—when it was Mr Hibbert himself who had, through his own actions and incautious use of language around his daughter, caused the distress she reportedly experienced. Mr Oakley further suggested that if minimising Eve’s distress was a concern for Mr Hibbert and Miss Gillbard they should never have brought the case to the High Court of Justice in the nation’s capital. The consequent media attention it would inevitably garner would not benefit Eve Hibbert, he argued.

Mr Oakley noted, at no stage throughout the trial had the prosecution ever alleged that Hall was “making things up.” It was only Mr Hibbert who made this allegation under cross-examination. Mr Oakley acknowledged that some may find Hall’s reports offensive but added that there was “cogency” to Hall’s honestly held beliefs.

Oakley highlighted the effect of the summary judgement. With regard to Hall’s “staged attack hypothesis,” and in light of Hall’s statement that he would revise his “theory” if evidence disproving it came to light, Mr Oakley observed that it was Hall who had requested the evidence that could have resolved the matter before proceeding to trial and it was the claimants who had denied Hall’s application for that evidence.

Oakley stated that Richard D. Hall has reported evidence and raised questions that have never been addressed. No ruling has ever examined the evidence Hall has unearthed. Should an injunction effectively censor Hall’s work, Mr Oakley suggested this would be “a very grave interference in the right to freedom of speech.”

Oakley noted that, regardless of the summary judgement, while under cross-examination, Hall had repeatedly described the City Room—Arena foyer where the bomb allegedly exploded—as a crime scene. Oakley asked the prosecution and the judge if they wanted Hall to return to the witness stand in order for the prosecution to examine the evidence Hall could present to substantiate his claim that the City Room was a crime scene.

Following a brief exchange between Mr Price and Mrs Justice Steyn, the court decided that it did not want to examine Hall’s evidence of a crime scene. Therefore Mr Oakley stated that Hall’s statement that the City Room was a crime scene should stand as a statement of fact because the High Court of Justice did not wish to question his assertion. This was a crucial point, because a reasonable defence against an allegation of harassment is that the course of conduct is undertaken to investigate or expose a crime.

Oakley stated there was no evidence, presented by the prosecution, to possibly substantiate the claim of harassment. He stated that Hall had conducted himself reasonably at all times, including passing his investigation and evidence to the investigating public inquiry.

Mr Oakley concluded that every aspect of Hall’s “course of conduct” fell “full square” under the description of the rational pursuit of evidence as outlined by Article 9 and Article 10 of the ECHR.

Oakley also noted that court rulings and the findings of UK public inquiries have often been successfully challenged or subsequently changed in light of the recognition of mistakes made or further evidence emerging. Mr Oakley cited the Post Office scandal, the Guildford Four and Birmingham Six trials and the Hillsborough inquiry as examples. Oakley suggested that at a future date, Hall’s unanswered questions needed be addressed and the evidence he presented accounted for.

Finally Mr Oakley concluded that if the intention was to seek an injunction effectively censoring Hall’s work it was a pointless exercise. As my book has now also been published, Mr Oakley noted that the information and evidence first reported by his client was now firmly in the public domain and nothing could stop that.

Mr Oakley referenced the new evidence I reported showing the fabrication of evidence presented to the public inquiry. If an injunction was sought to censor all criticisms, Oakley asked if it would therefore be necessary to place an injunction on the entire population.

Shortly before the trial concluded, Mrs Justice Steyn gave the prosecution the final chance to respond to Mr Oakley’s summation.

Mr Price said that the fact that Mr Hall had brought his investigation and the evidence to the attention of the official inquiry panel was not germane to “detecting a crime” because this wasn’t raised by the prosecution as an element of their harassment claim. He again stated that Mr Hall had not, in any event, presented any evidence that the publication of his book—and documentary—constituted investigation of a crime.

Of course there is a reason why Hall didn’t present this evidence: the summary judgement. When Mr Oakley offered the prosecution the opportunity to examine that evidence in the trial, they declined to do so.

Mrs Justice Steyn Asked Mr Price to clarify what the issue of Mr Hall’s so-called “followers” had to do with the case. This had been repeatedly raised by the prosecution and its witnesses, most notably Mr Hibbert.

A number of Richard’s supporters, myself included, had been present throughout the trial. Mr Hibbert testified that the he found our presence, both during this trial and the preceding summary judgement, “intimidating.” Though Mr Hibbert conceded that open access justice was important.

In reply to Mrs Justice Steyn, Mr Price said that the issue of Mr Hall’s purported “followers” was not particularly relevant to the prosecutions case. One has to wonder, then, why they kept mentioning it.

Mr Justice Steyn said that she would begin her deliberations and provide her ruling at the start of the “next term.” I believe this is in early October.

I do not speak for anyone else but, having sat through this bizarre trial, I’m sure others share my hope that justice will ultimately prevail.

This is masterly court reporting, on a par with the defence counsel's superb conduct. Bravo.

Overall, regarding RDH's chances, I'm reminded of the lyric:

"Everybody knows that the dice are loaded

Everybody rolls with their fingers crossed."

I mentioned Jo Cox in a previous part comment. Funny how noone has come after Hall for his analysis of this false flag. Bizarro world is real. Steyn is following orders from above.