*******************************************

I have not received any encouragement or inducement from anyone to write about or discuss any information related to the Manchester Attack. All research discussed is exclusively my own and based solely upon information freely available in the public domain.

*******************************************

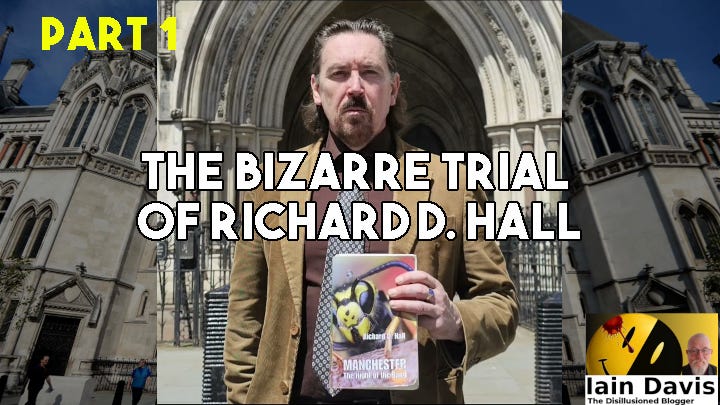

Over the next few days I’ll report on the evidence and arguments presented at the trial of Martin Hibbert & Eve Hibbert and Richard D. Hall held at the Royal High Court of Justice in London. The report is based upon my hand written notes. A subsequent transcript of the proceedings could provide more detail. Any errors made in this series are my own.

The four day trial commenced on the 22nd July 2024 and concluded at lunch time on the fourth day.

To say the trial was unusual would be putting it mildly. Frankly, had I not been sat in the court observing and listening to proceedings I would have found it hard to believe it happened.

I will try to be as objective as possible but I am not impartial. I support Richard D. Hall and have recently published my own book The Manchester Attack: An Independent Investigation exploring not only the evidence which shows that the so-called Manchester Arena bombing did not happen—there was no bomb—but also the propaganda environment within which this trial resides.

PDF copies of my book are FREE to all subscribers to my website. Similarly, PDF copies of Richard’s book Manchester: The Night of the Bang are available for FREE.

You can support Richard by purchasing a copy of his book or donating to his legal fund. As I am sure you can appreciate, bringing a case to the High Court and defending yourself against a High Court claim is extremely expensive. If Richard loses—and we have every reason to hope that he won’t—the damages, costs and injunctions sought by the claimants could be ruinous for Hall.

Building upon Richard’s investigative journalism, I have found additional damning evidence which further corroborates Hall’s conclusion that there was no bomb and, therefore, it is not possible that anyone was killed or harmed inside the City Room—the foyer of the Manchester Arena—as claimed in the official account.

Most people familiar with the state’s narrative about the Manchester Arena bombing will understandably baulk at the assertion there was no bomb. The notion that the state or elements within the state hoaxed the Manchester Arena bombing sounds and appears preposterous. All any of us can do is look at the evidence we have available. Incredulity is not evidence of anything.

To give you an idea of what the physical evidence shows and how it refutes the official account of the bombing I will briefly mention the “merchandise stall.” As reported by Richard D. Hall, an alleged Manchester Arena “survivor” Josie Howarth, who was reportedly severely injured by shrapnel from Salman Abedi’s suicide bomb and spent five weeks in hospital as a result, said the following:

We’d been sat waiting for the concert to end on some steps near the entrance. When the music stopped we stood up and went towards the foyer. Then the next thing I know, there was an explosion and the merchandise stand blew to pieces.

Below is a still image of the merchandise stall (stand) captured inside the City Room (foyer) of the Arena around four minutes after the bomb is said to have detonated. As you can see the merchandise “stand”—supposedly six to eight metres away from the epicentre of a massive TATP shrapnel bomb—is entirely intact, undamaged, and even undisturbed. As are the posters hanging on the wall behind it.

I am not going to speculate why Josie Howarth’s account is evidently false. Possible motivation is explored in my book. These articles will be about the trial and the evidence and arguments presented at the trial.

The trial was covered by, among other journalists, ITV’s Granada Reports Correspondent Elaine Willcox. She makes some unsupported statements about alleged facts based upon her unquestioning acceptance of the state narrative. Nonetheless, Elaine Willcox did report some important aspects of the trial.

Following the conclusion of the trial one of the claimants—who it transpired was effectively the sole claimant—Mr Martin Hibbert read out a prepared statement:

We live in a society where free speech and the right to express a genuinely held opinion must be protected, but when those beliefs and actions are inaccurate, offensive and damaging, and cause harm to those who have already suffered so badly, people must be challenged. [. . .] Actions that in this case have led to further anxiety and distress.

To a great extent I agree with Mr Hibbert. Freedom of speech and the right to express a genuinely held opinion must be protected if we want to live in a so-called representative democratic society. I would go further than Mr Hibbert. In my view all “genuinely held opinion,” no matter who holds or expresses it, “must be challenged.”

It is the middle clause of Mr Hibbert’s statement where my own doubts start to creep in. Inaccuracy can only be established by examining the evidence. To simply state something is either inaccurate or indeed accurate, without examining the evidence, is an opinion but only the evidence can substantiate or contradict it.

To be clear: the evidence that Hall reported and the subsequent evidence that I have added has never been examined or even acknowledged in any official investigation or inquiry into the Manchester Arena bombing. For instance, it was assumed that the merchandise stall must have been destroyed by a bomb. The observable physical evidence—which shows that it was not—has never been mentioned, let alone examined or explained, in any official report or account.

Sure, people are free to believe whatever they like but they cannot simply demand their opinion be believed, or taken as fact, by anyone else. Especially if the evidence contradicts their stated belief, opinion, or statement of alleged fact. Mr Hibbert’s assertion that Hall’s opinions are “inaccurate” is not supported by the observable, physical evidence. Mr Hall’s opinions and stated beliefs appear to be.

As we shall discuss over the next couple of articles, Mr Hibbert’s claim that the offence he has taken from Hall’s questioning of the official account is damaging and specifically that Hall’s reporting causes “harm” is evidently the crux of the prosecutions argument. It should be noted that this notion of “harm” caused by words or publications is a new concept that has been introduced through legislation such as the UK Online Safety Act 2023 (OSA) and the EU’s Digital Services Act (DSA).

Precisely what constitutes “harm” is not defined in either act. In the OSA Section 234 we get a definition of “harm,” as it applies to the Act:

“Harm” means physical or psychological harm.

That is to say “harm,” perhaps unsurprisingly, means “harm.”

The dictionary definition of “harm” means to cause some sort of “physical or other injury or damage.” To physically assault someone, for example, is to injure them thus causing “harm.” Black’s Law Dictionary defines harm as “to damage, injure or hurt.” Again, when we are talking about physical “harm” the meaning is abundantly clear.

It is when we get to claimed “psychological” injury that things start to get much more subjective. For the purposes of the OSA, it introduces the idea of harmful “content” where content is information “repeatedly encountered” by the alleged sufferer of said “harm.”

Therefore the OSA suggests that “harm” is incurred by the harmed individual when they repeatedly encounter information that supposedly causes them to “act in a way that results in harm to themselves or that increases the likelihood of harm to themselves.”

Leaving aside that “harm” itself is a somewhat ambiguous term in the OSA, the inference is clearly that the recipient of the information—content—bears no responsibility for repeatedly encountering that information. Further, any acts of self-harm they then commit are not their responsibility either but rather the responsibility of the author of the information—or content—which, presumably, the recipient is powerless to avoid or resist.

If we take nasty comments made to us on social media as an example, the OSA suggests that if we are offended or hurt by those comments and then harm ourselves—perhaps because our self esteem has collapsed as a result—that is the responsibility of the “content” author, not us for harming ourselves. Of course, the question arises why we wouldn’t simply block that “harmful” content or avoid using the platform causing us alleged “harm” rather than continue to expose ourselves to it. The OSA is clearly an attempt to shift all responsibility from the recipient to the purveyor of information.

The other aspect of so-called “harm” suggested by the OSA stipulates that “harm” is also caused where the content leads others to “do or say something to another individual that results in harm to that other individual or that increases the likelihood of such harm.”

Under the Serious Crimes Act 2007, where “encouraging or assisting the commission of an offence” is proscribed, the link between the publication of content and causing actual, legitimate harm is relatively simple to establish and understand. For example, if I published an article urging readers to burn down someone’s house then obviously I would have encouraged others to commit offences and put the homeowner at increased risk of real, physical harm. We have traditionally called such direct attempts to encourage criminality, through published information, “incitement.” UK laws already exist to deal with this kind of genuinely dangerous publication—or “content.” The OSA adds nothing to those laws.

Clearly, the OSA is not talking about “incitement” to commit offences. Instead it is evidently applying the same standard of “encouragement”—found in the Serious Crimes Act—to published content that some individuals may subsequently cite as claimed justification, not for committing offences but for allegedly causing “harm”—whatever that is.

This aspect of the OSA represents an even greater shift in responsibility from individuals who interact with each other online to the publishers of critical information—in the literary sense. Not only is the author of the criticism responsible for acts of the person they have criticised they are also responsible for the acts of others who, having read, listened to or viewed such “content,” decide to act in a way deemed to constitute causing “harm.”

If we pause to think about this for a moment, the implications in a supposed democratic society are truly chilling. Individuals may well be prosecuted if they publish anything that someone else perceives to be “harmful.” Under such legislation J. D Sallinger would have been found guilty of causing “harm” because Mark David Chapman imagined his reading of The Catcher in the Rye somehow justified him murdering John Lennon.

In Chapman’s case at least we can identify the “harm” caused. The concept of harm touted in the OSA and the DSA, for example, is far more nebulous. In fact, it appears to be entirely subjective.

I receive a fair amount of nasty comments. They do not affect me particularly purely because I do not perceive them as harmful. If, however, I was depressed or at a low ebb I could perceive exactly the same comments as “harmful” and I may take some self-harming action as a result. This would have absolutely nothing to do with the nature of the comments and everything to do with my changed subjective interpretation of them.

It is therefore very difficult to see how a court could objectively rule on the application of the provisions in the OSA. What is required, in a Common Law jurisdiction such as the UK, is a case precedent upon which to base any future determination of OSA “harm.” A test case is required and it appears that the trial of Richard D. Hall may form part of the process of setting case precedents.

While the case was said to be a civil claim of alleged harassment and GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation) breaches, as the case progressed it seemed to morph into something else. It was very notable that, in his summation of the prosecution’s case, Mr Hibbert’s prosecuting barrister, Mr Jonathan Price, was keen to explore the implication the possible verdict may have with regards to the UK court’s interpretation of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR).

If we consider that the OSA appears to represent what amounts to censorship legislation, the possibility exists that future rulings based upon it could fall foul of Article 10 of the ECHR which guarantees “freedom of expression.” Therefore, it is not unreasonable to suppose that some case law precedent needs to be set in order to determine the UK legal system’s applied limits of freedom of expression with regard to the ECHR.

I am not a legal scholar, and the intricacies of the legal arguments will have been better understood by those with a fuller appreciation of the law. But, from a layman’s perspective, this appeared to me to be what Mr Price was discussing in his summation.

Unavoidably it seems, this is the kind of consideration the trial judge, Mrs Justice Steyn, will have to wrestle with in her ruling on what was referred to by the prosecution to be an “exceptional case.” It is reasonable that the prosecution would have recognised and highlighted this is their summation. That said, it is also reasonable to state that the prosecution did not focus on the evidence presented at the trial to the extent Hall’s defence barrister, Mr Paul Oakley, did in his summation. Or, indeed, throughout the trial for that matter.

Mrs Justice Steyn has to consider the evidence presented by both the prosecution and the defence. She faces the difficult task of balancing freedoms, rights and responsibilities while simultaneously judging the veracity or extent of the alleged harm claimed. In particular, the prosecution recognised that the future determination of the boundaries of said freedoms, rights and responsibilities could be redrawn by her ruling to some extent.

Nonetheless, with specific regard to the claim of harassment and GDPR breaches, the evidence presented at the trial certainly gives those of us who support Richard D. Hall reason for hope.

In this “exceptional” context, the rest of Mr Hibbert’s prepared statement, delivered after the conclusion of the trial, is interesting:

We shouldn’t have to face such allegations that the Manchester Arena attack never happened, and that our injuries were not as a result of the bombing – we certainly shouldn’t have needed to be here in court to make a stand and to protect others from this kind of behaviour.

Mr Hibbert raises a very salient point. He is talking about people who claim to have experienced unimaginable suffering. Should the fact that they claim this degree of pain and loss preclude their accounts from ever being questioned by anyone?

Is it reasonable that we, as a society, accept the severity of the claim, and not the evidence, to be a determining factor for establishing its credibility? If so, where should we draw that line?

Is it OK to question a mother who claims to have suffered the loss of a miscarried child but not a mother who claims her child was murdered? What is the point at which a claim of distress and pain renders any questioning of that claim unacceptable?

Mr Hibbert continued:

For many families affected by the bombing it is a struggle every day, even now more than seven years on, to comprehend what happened, and the impact it has had on their lives. They should never have to face such hurtful claims and I hope this case sends out a clear message that it will not be tolerated.

Certainly Mr Hibbert has made it very clear that he will not “tolerate” any questioning of his or other Manchester survivor’s accounts. Mr Hibbert has become an outspoken advocate for the rights of the Manchester Arena “victims,” such as Josie Howarth.

In Part 2 we’ll start looking at the evidence presented in the trial.

We know the standards that are being applied to Richard D Hall as an independent journalist are not and will not be applied to the main stream journalists . The actions of Marianna Spring in sending many emails to Richard and door stepping him after he had informed them he did not wish to be contacted. Is a far more obvious case of harassment.

I am reminded of the case of Brenda Leyland who was door stepped by a Sky reporter and publicly shamed in the media. She committed suicide as a result "Jonathan Levy, senior manager at Sky News, said the approach was in line with the broadcaster’s guidelines on doorstepping: deemed to be warranted when public good outweighed intrusion, and as long as the method was proportionate."

"The team at Sky News followed its editorial guidelines and pursued a story in a responsible manner that we believed was firmly in the public interest.”"

What harm does Martin Hibbert claim he suffered by encountering Richards work.

Martin has said he was first told about it and only after a time did he find out more .

It is not clear if Martin himself watched or read any of Richards work.. Some of his statements indicate more that it is what he has been told. But did not talk until recently of it causing him any distress.

It is said that any corrupt organisation arranges rules to protect itself. Like most rules it is more the threat than reality. But occasionally a high profile enforcement is required to maintain the fear and thus self policing that the rules intend.

The Jo Cox video was well done too. No way it went down the way they said.