The United Nations (UN) enables global governance and centralises global political power and authority. No national electorate on Earth has ever given their democratic mandate for the UN to create a global governance regime to serve the interests of private capital. But that is precisely what it has done.

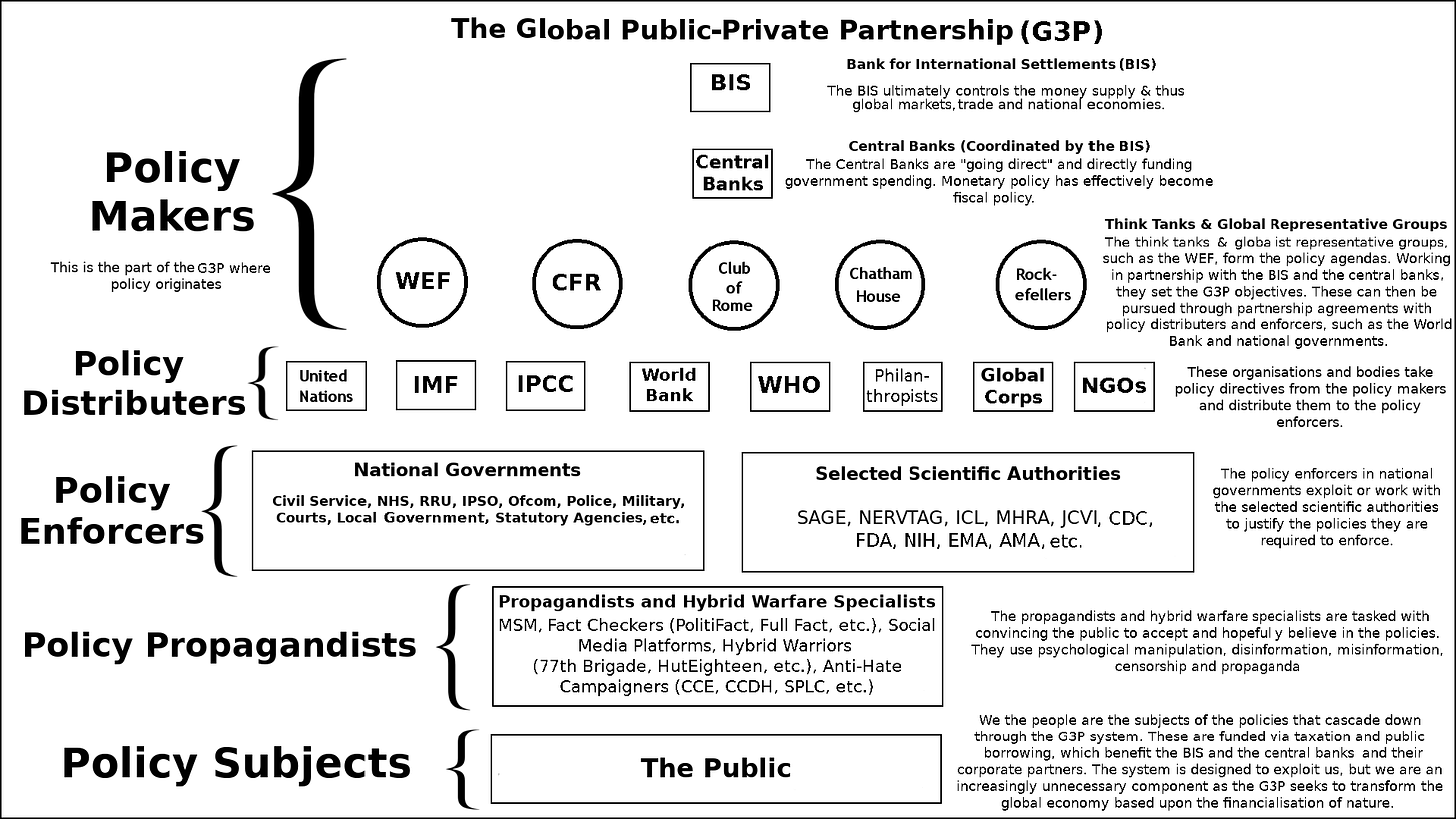

Any nation, or bloc of nations, that bids for dominance within the United Nations’ regime is seeking to maximise its, or their, influence. But they can never lead the UN because it represents the interests of a global public-private partnership (G3P) dominated by oligarchs, not nation states or their respective populations.

In the recent BRICS XV Johannesburg II Declaration, the member states collectively announced:

We reiterate our commitment to inclusive multilateralism and upholding international law, including the purposes and principles enshrined in the Charter of the United Nations (UN) as its indispensable cornerstone, and the central role of the UN in an international system in which sovereign states cooperate.

The BRICS are seeking reform of the UN Security Council in an attempt to load it in their favour. While some might consider this preferable to the current situation, notably neither the governments of China nor Russia are suggesting they forego their Security Council veto powers.

The BRICS initiative has already been countermanded by the NATO/G7 aligned efforts, led by the globalist think-tank Chatham House, to accept India and Brazil as permanent members of the UN Security Council, but offset it with the addition of Germany and Japan.

Moreover, just like the G7/NATO alliance countries, the BRICS maintain their joint commitment to the UN Charter. The Charter is not the wonderful, emancipating constitution for humanity that the UN and governments would have us believe. On the contrary, it is a key document for the establishment of a system of global tyranny, where nation states are relegated to vassals of an international Criminocracy.

Article 2 of the United Nations Charter declares that the UN is “based on the principle of the sovereign equality of all its Members.” The Charter then goes on to list the numerous ways in which nation-states are not equal. It also clarifies how they are all subservient to the UN Security Council in matters of international “security.”

Despite all the UN’s claims of lofty principles—respect for national sovereignty and for alleged human rights—Article 2 declares that no nation-state can receive any assistance from another as long as the UN Security Council is forcing that nation-state to comply with its edicts. Even non-member states must abide by the Charter, whether they like it or not, by decree of the United Nations.

The UN Charter is a paradox. Article 2.7 asserts that “nothing in the Charter” permits the UN to infringe the sovereignty of a nation-state—except when it does so through UN “enforcement measures.” The Charter declares, apparently without reason, that all nation-states are “equal.” However, some nation-states are empowered by the Charter to be far more equal than others.

While the UN’s General Assembly is supposedly a decision-making forum comprised of “equal” sovereign nations, Article 11 affords the General Assembly only the power to discuss “the general principles of co-operation.” In other words, it has no power to make any significant decisions.

Article 12 dictates that the General Assembly can only resolve disputes if instructed to do so by the Security Council. The most important function of the UN, “the maintenance of international peace and security,” can only be dealt with by the Security Council. What the other members of the General Assembly think about the Security Council’s global “security” decisions is a practical irrelevance.

Article 23 lays out which nation-states form the Security Council:

The Security Council shall consist of fifteen Members of the United Nations. The Republic of China, France, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics [Russian Federation], the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, and the United States of America shall be permanent members of the Security Council. The General Assembly shall elect ten other Members of the United Nations to be non-permanent members of the Security Council. [. . .] The non-permanent members of the Security Council shall be elected for a term of two years.

The G7/NATO alliance and the BRICS alliance are ostensibly vying for supremacy within the UN Security Council. Each side is competing for a bigger slice of regime pie. No one is suggesting that the the pie should be thrown in the bin and a new one baked.

The General Assembly is allowed to elect “non-permanent” members to the Security Council based upon criteria stipulated by the Security Council. Currently the “non-permanent” members are Albania, Brazil, Ecuador, Gabon, Ghana, Japan, Malta, Mozambique, Switzerland and United Arab Emirates.

Article 24 proclaims that the Security Council has “primary responsibility for the maintenance of international peace and security” and that all other nations agree that “the Security Council acts on their behalf.” The Security Council investigates and defines all alleged threats and recommends the procedures and adjustments for the supposed remedy. The Security Council dictates what further action, such as sanctions or the use of military force, shall be taken against any nation-state it considers to be a problem.

Article 27 decrees that at least 9 of the current 15 member states must be in agreement for a Security Council resolution to be enforced. All of the 5 permanent members must concur, and each has the power of veto. Any Security Council member, including permanent members, shall be excluded from the vote or use of its veto if they are party to the dispute in question.

UN member states, by virtue of agreeing to the Charter, must provide armed forces at the Security Council’s request. In accordance with Article 47, military planning and operational objectives are the sole remit of the permanent Security Council members through their exclusive Military Staff Committee. If the permanent members are interested in the opinion of any other “sovereign” nation, they’ll ask it to provide one.

The inequality inherent in the Charter could not be clearer. Article 44 notes that “when the Security Council has decided to use force” its only consultative obligation to the wider UN is to discuss the use of another member state’s armed forces where the Security Council has ordered that nation to fight or act in a “peacekeeping” capacity. For a country that is a non-permanent member of the Security Council, use of its armed forces by the Military Staff Committee is a prerequisite for Security Council membership.

The UN Secretary-General, identified as the “chief administrative officer” in the Charter, oversees the UN Secretariat. The Secretariat commissions, investigates and produces the reports that allegedly inform UN decision-making. The Secretariat staff members are appointed by the Secretary-General. The Secretary-General is “appointed by the General Assembly upon the recommendation of the Security Council.”

Under the UN Charter, then, the Security Council represent the regime’s enforcers. This arrangement affords the governments of its present permanent members—China, France, Russia, the UK and the US—considerable additional authority over every other nation. There is nothing egalitarian about the UN Charter.

However, when it comes to matters beyond the use of military force, the enforcement of economic sanctions or other “punishments,” even the permanent members of the Security Council are no more than “enabling partners.”

The UN was created, in no small measure, through the efforts of the private sector Rockefeller Foundation (RF). In particular, the RF’s comprehensive financial and operational support for the Economic, Financial and Transit Department (EFTD) of the League of Nations (LoN), and its considerable influence upon the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA)—the foundational UN “organisation.” The RF was the key player in the transformation of the LoN into the UN.

The UN came into being as a result of public-private partnership. Since then, especially with regard to defence, financing, global health care and sustainable development, public-private partnership has come to dominate the UN system.

The UN is no longer an intergovernmental organisation, if it ever was one. It is a global collaboration between governments and a multinational infra-governmental network of private “stakeholders.”

In 1998, then-UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan told the World Economic Forum’s Davos symposium that a “quiet revolution” had occurred in the UN during the 1990s:

[T]he United Nations has been transformed since we last met here in Davos. The Organization has undergone a complete overhaul that I have described as a “quiet revolution”. [. . .] [W]e are in a stronger position to work with business and industry. [. . .] The business of the United Nations involves the businesses of the world. [. . .] We also promote private sector development and foreign direct investment. We help countries to join the international trading system and enact business-friendly legislation.

In 2005, the World Health Organisation (WHO), a specialised agency of the UN, published a report on the use of information and communication technology (ICT) in healthcare titled Connecting for Health. Speaking about how “stakeholders” could introduce ICT healthcare solutions globally, the WHO noted:

Governments can create an enabling environment, and invest in equity, access and innovation.

In its 2013 exploration of the Post-2015 Development Agenda (Agenda 2030), the UN said:

Partnership can promote a more effective, coherent, representative and accountable global governance regime, which should ultimately translate into better national and regional governance [. . .]. In a more interdependent world, a more coherent, transparent and representative global governance regime will be critical to achieve sustainable development in all its dimensions. [. . .] A global governance regime, under the auspices of the UN, will have to ensure that the global commons will be preserved for future generations.

The UN is not merely an intergovernmental organisation. It considers itself to be the lead organisation in a “global governance regime.” In turn, the regime is the expression of the G3P. The UN regime empowers global governance led by an international oligarchy.

In 2014, the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN-DESA) defined “global governance” in its publication Global Governance and the Global Rules For Development in the Post 2015 Era:

Current approaches to global governance and global rules have led to a greater shrinking of policy space for national Governments [. . . ]. Global governance has become a domain with many different players [. . .]. Included are [the] activities of the private sector, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and large philanthropic foundations (e.g., Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, Turner Foundation) and associated global funds to address particular issues[.] Participation of several actors is noticeable, for instance, in public health with the emergence of global health partnerships

The 2015, Adis Ababa Action Agenda conference on “financing for development” clarified the nature of an “enabling environment.” National governments from 193 UN nation-states committed their respective populations to funding public-private partnerships for sustainable development by collectively agreeing to create “an enabling environment at all levels for sustainable development;” and “to further strengthen the framework to finance sustainable development.”

In 2017, UN General Assembly Resolution 70/224 (A/Res/70/224) compelled UN member states to implement “concrete policies” that “enable” sustainable development. A/Res/70/224 added that the UN:

[. . .] reaffirms the strong political commitment to address the challenge of financing and creating an enabling environment at all levels for sustainable development [—] particularly with regard to developing partnerships through the provision of greater opportunities to the private sector, non-governmental organizations and civil society in general.

In short, the “enabling environment” is a government, and therefore taxpayer, funding commitment to create markets for the private sector to exploit. Over the last few decades, successive Secretary-Generals have overseen the UN’s formal transition into a global public-private partnership (G3P).

The role of national governments is to “translate” the policy agenda created by the G3P regime into national policy and legislation. For example, Agenda 21 was devised by globalist think-tanks in 1992 and underpins today’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). These have been “translated” by national governments into “net zero” policy strategies. Elected governments don’t devise the policy agenda, they merely implement it.

Nation-states do not have sovereignty over public-private partnerships. Sustainable development is just one policy agenda that relegates government to the role of an “enabling” partner that sits within a global network comprised of multinational corporations, non-governmental organisations (NGOs), civil society organisations and other actors. The “other actors” are predominantly the philanthropic foundations of individual billionaires and immensely wealthy family dynasties—that is, global oligarchs.

For example, the “global funds to address particular issues,” highlighted in 2014 by UNDESA, include the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ). Launching GFANZ in 2021 at the COP26 climate change summit in Glasgow, King Charles III—then Prince Charles—made it abundantly clear who is leading the global governance regime’s policy agendas:

The scale and scope of the threat we face call for a global systems level solution based on radically transforming our current fossil fuel based economy. [. . .] So ladies and gentleman, my plea today is for countries to come together to create the environment that enables [the enabling environment] every sector of industry to take the action required. We know this will take trillions, not billions of dollars. [. . .] [W]e need a vast military style campaign to marshal the strength of the global private sector, with trillions at [its] disposal far beyond global GDP, and with the greatest respect, beyond even the governments of the world’s leaders. It offers the only real prospect of achieving fundamental economic transition.

Effectively, then, the UN serves the interests of private capital. Not only is it a mechanism for the centralisation of global political authority, that political authority delivers global policy agendas that are “business-friendly.” That means multinational corporation-friendly.

Such agendas may happen to coincide with the best interests of humanity, but where they don’t—which is largely the case—well, that’s just too bad for humanity.

The United Nations Charter empowers a global public-private partnership to exercise global governance. Nation states are relegated to “enabling partners” that are allowed to translate G3P policy initiatives into national policy.

The suggestion that the UN Charter enshrines “the sovereignty of nation states” and acts as some sort of wedge against the global tyranny of oligarchs is utterly ridiculous. The UN Charter is the embodiment of the centralisation of global power and authority delivered into the hands of private “actors.”

The UN was rigged from the start to enable this nonsense.

Having a security council with the ability for one of the few members to veto anything is ridiculous.

It's a fake democracy.... "some are more equal than others" - Animal Farm by Orwell

Thank you for your exhaustive work Iain.